The Crown Council Today

The structure and role of the Crown Council of Ethiopia

The Crown Council of Ethiopia is the Constitutional Body which advises the reigning Emperors of Ethiopia and, during an interregnum (such as now), actually acts as the Crown. The Council’s members are initially appointed by an Emperor, and subsequently (during an interregnum) sustained in their posts or replaced under the direction of the President of the Council.

The information on this page is based in part on material published in 1998 in the book, Ethiopia Reaches Her Hand Unto God: Imperial Ethiopia’s Unique Symbols, Structures, and Role in the Modern World, by Gregory Copley, and published by The International Strategic Studies Association, Washington DC.

The Dergue, which grabbed power illegally and by force, and which had no legitimacy or historic or legal claim or right to office or authority, declared in March 1975 that it had deposed Emperor Haile Selassie I. Significantly, the Dergue announced that, having deposed Emperor Haile Selassie, it now recognised as Negus (King) the legitimate and constitutional successor to the throne, Crown Prince Asfa Wossen, who was in Geneva at the time for medical treatment. An announcement by the Dergue said that Crown Prince Asfa Wossen would be crowned King (Negus) immediately upon his return to Ethiopia. But the civil war and terror which swept over Ethiopia precluded any return by the Crown Prince who, having suffered a serious stroke, could not at that time travel.

By the time he was sufficiently well, it became clear that the Monarchy could not displace the Dergue for the moment because of the purge of former Government officials, the ongoing war and Soviet involvement. Under such circumstances, the Crown Prince could not return home.

The internationally- and historically-recognised Monarch and Monarchy did not abdicate; nor did the legal Constitution change, but the illegal act of an outlaw power group effectively altered the realities on the ground in Ethiopia. The subsequent military victory finalised against the Dergue on May 27, 1991, by guerilla fighters of the Tigré People’s Liberation Front (TPLF), a Tigrean organisation riding into Addis Ababa with two divisions of Sudanese armour (much as Tito had ridden into Belgrade in 1945 atop Soviet Red Army T-34 tanks), meant that a new de facto and unelected, unrepresentative power had come into control of Ethiopia.

The international community had what it felt were more important things to ponder in the middle of 1991 than the restoration of Ethiopian legitimacy. The collapse of the Soviet Union, the Dergue’s backers, meant that all attention was focused on the break-up of the Soviet empire and the spin-offs from that, including the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait in August 1990.

After 17 years of bloodshed and anguish in Ethiopia, a distracted international community — led, as far as Ethiopian discussions were concerned, by Britain and the US — allowed the TPLF to attempt to build an interim national administration in the country. [The TPLF later reconstituted itself, mostly for the purpose of retaining power over all of Ethiopia, to the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF).] The United States, in particular (and under then US Assistant Secretary of State for Africa Herman Cohen), stood by the TPLF leader, Meles Zenawi, and allowed him to consolidate power, riding roughshod over the claims and positions of other groups. In reality, the US and UK had few options; they were preoccupied with the break-up of the Soviet Empire and the emergence of troublesome leaders elsewhere, particularly Iraqi President Saddam Hussain’s military lunge at Kuwait, which required all the efforts of the US Bush Administration to control. Ethiopia’s restoration to traditional and democratic government was one of the casualties of this situation, as was the Liberian civil war on Africa’s West Coast. The US, totally focusing its resources on Iraq and Kuwait, asked Nigeria to handle the Liberian war.

But as a result of the TPLF victory, the Tigrean leadership also acceded to the wishes of their Eritrean fellow rebels fighting to make Eritrea independent. Eritrea formally seceded from Ethiopia in 1993. TPLF leader Meles Zenawi declared himself President of Ethiopia in July 1991 and moved to consolidate this de facto leadership with a series of carefully-orchestrated elections which occurred during a process of strict suppression of opposition voices and strong moves to stop the Monarchy from returning to the office and station it had held for three millennia. [Meles Zenawi’s subsequently changed his Administration’s structure, placing power in the hands of a Prime Minister, which he himself became, making the presidency ceremonial.] The TPLF had originally cast the Monarchy as one of the options in its proposed new constitution. But it was clear that the TPLF had merely inserted the Monarchy as an option only to be able to immediately dismiss it, as though it had been proffered to the people for debate. It had not. There was no possibility at that time of any popular discussion of the option, and the TPLF — which transformed into the EPRDF — ramrodded its “constitution” into effect without due process. The object was solely to give a patina of domestic and international legitimacy to the new EPRDF constitution. The so-called constitutional consultative assemblies were fraught with many problems during this highly-unstable period, and the EPRDF, as the ruling party de facto, made sure that no chance was given to any option other than those which it chose.

It is significant to note that the Monarchy has not relinquished its role and duties in Ethiopia. Since 2004, the Crown Council has redefined the role that a Constitutional Monarchy can play in Ethiopia that is much more in line with the role that constitutional Monarchs play in other countries.

It seems clear that had the exiled Crown Prince Asfa Wossen been physically fit, then the Monarchy could have taken a far greater rôle in ousting the Dergue and restoring legitimate government to Ethiopia in 1991 or earlier. The Crown Prince had been abroad during the 1974 coup receiving medical treatment for a stroke, brought about by complications from diabetes in 1973.1The Passing of An Era: A Short Biography of Emperor Amha Selassie I (1916-1997), in Ethiopian Review, January-February 1997.

.

Indeed, the Dergue’s removal was only possible in 1991 because of the withdrawal of Soviet support from it, brought about by the collapse of the USSR itself. The TPLF was not Ethiopia’s saviour; the NATO-led escalation of the Cold War against the Soviet Union had merely robbed the Dergue of its benefactor. History will show that Crown Prince Asfa Wossen’s physical disabilities — he was heavily paralysed from the stroke until the time of his death in 1997 — played a decisive rôle in Ethiopia’s history.

Despite being in exile in London, Crown Prince Asfa Wossen was persuaded, in 1988, to declare himself Emperor, taking the throne name Amha Selassie I. But this act, which showed that the Monarchy was still alive and evolving, did not have enough power behind it — because of the new Emperor’s poor health — to have sufficient political impact inside Ethiopia to bring about change on the ground. Emperor Amha Selassie did have the authority, under the Constitution of the internationally-recognised Government of Emperor Haile Selassie, to reconvene the Crown Council.

Writers Chris Prouty and Eugene Rosenfeld noted in their comprehensive Historical Dictionary of Ethiopia and Eritrea:2Prouty, Chris, and Rosenfeld, Eugene: Historical Dictionary of Ethiopia and Eritrea. 2nd Ed. 1989, Metuchen, New Jersey, and London: Scarecrow Press “Rulers in ancient times [in Ethiopia] usually had a close circle of people they trusted and consulted, but a Crown Council as such was named as an advisory body to the Emperor only in the revised Constitution of 1955. It was in existence since 1941… In 1966 new members were named. It was revived as the consultative body for the Emperor.”

It was given fresh life once again by Amha Selassie’s promulgation of July 15, 1993, appointing new names to the Council to give it the vitality to undertake meaningful actions to help Ethiopia. Clearly, the members of the Crown Council convened under Emperor Haile Selassie were no longer able, because of the civil war, to be brought together, although the institution of the Crown Council — like the Crown itself — retained its legal rôle.

The reconstruction of the Crown Council may have been Emperor Amha Selassie’s most significant contribution to Ethiopia after the 1974 coup. It was done with considerable deliberation and consultation, spearheaded by Afe-Negus Teshome Haile-Mariam, the former Chief Justice of Ethiopia under Emperor Haile Selassie I. He had been commanded by the new Emperor to canvas the Ethiopian community, inside and outside the country, for names to consider for the Council, and it was after an extensive procedure and series of discussions with the Emperor that a slate was put forward for consideration and, ultimately, acceptance on July 15, 1993, when His Majesty signed the document reconstituting the Council.

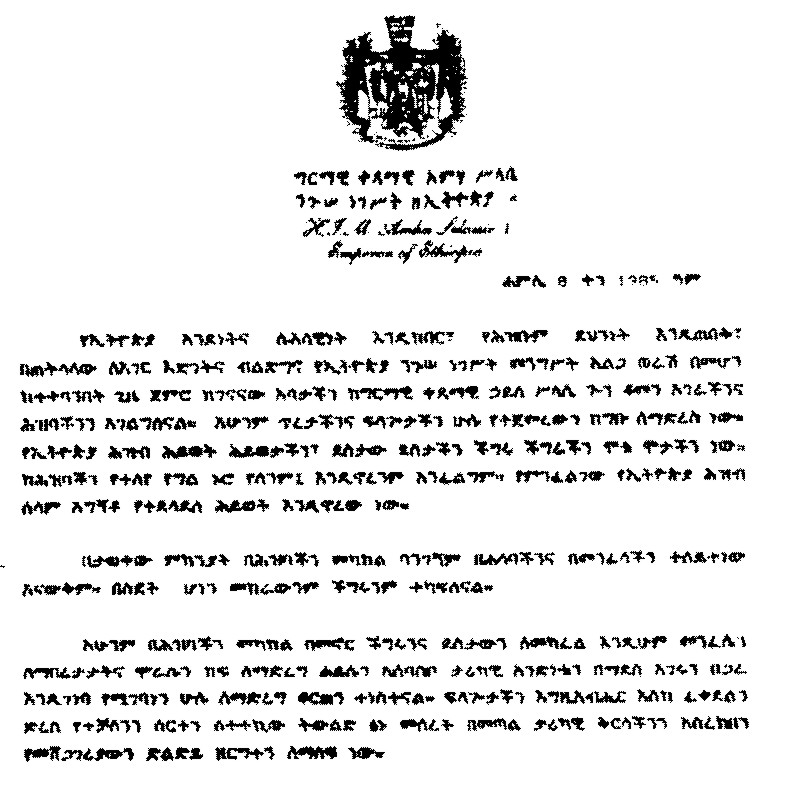

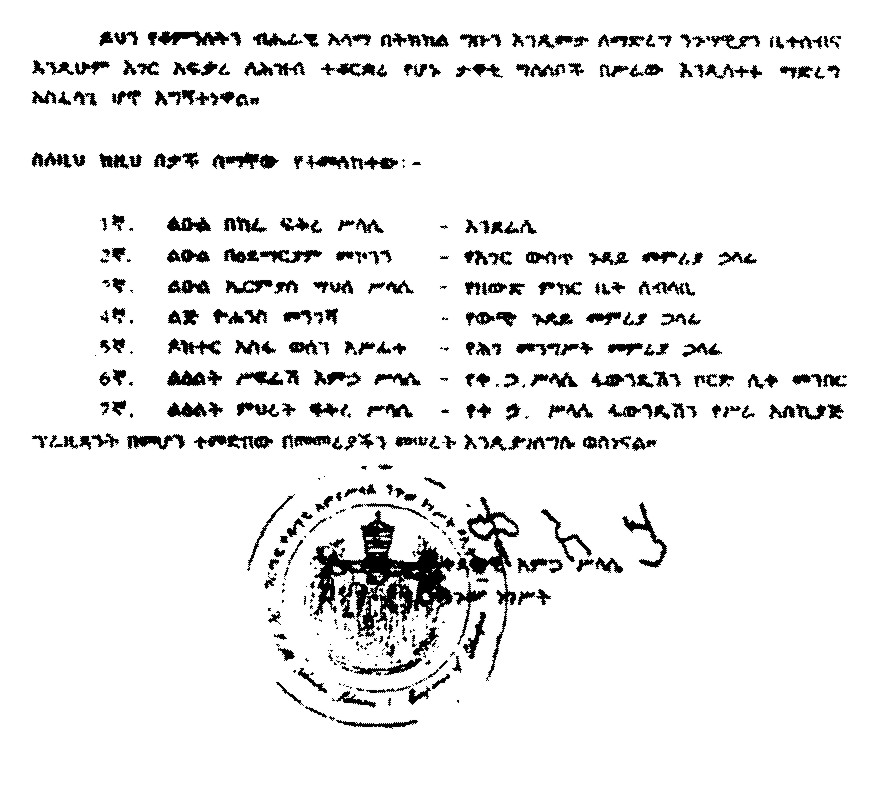

In the document of Appointment of the Ethiopian Crown Council 3Appointment of the Ethiopian Crown Council, English Translation, dated July 15, 1993. See illustration of the Amharic original shown here. His Majesty Ahma Selassie I said:

In order for Ethiopian sovereignty and unity to be respected, for the People’s well-being to be protected, and for the overall growth and development of our nation, we have strived ever since our appointment as Crown Prince of the Imperial Government of Ethiopia to serve our country and People as did the august Father His Imperial Majesty Haile Selassie I. The Ethiopian People’s life is our life; their happiness, ours; their suffering, our burden; their death, ours. We have no independent life apart from our People, neither do we wish it. What we wish and aspire for is for the Ethiopian People to live in peace and harmony. It is our current intention and wish to see to it that what we have started reaches fruition.

For well-known reasons, even if we are not amidst our People, we have never left them in spirit. In exile, we have shared our People’s tribulation and suffering.

Even now, we have firmly decided and are determined to be amidst our People to share with them their problems and to partake in their joys as well as to give them moral support, to facilitate their unity of purpose and to preserve their historical unity and for the People to rise and reconstruct our nation. It is our wish that for such as the Lord permits us, we will do all we can to leave for future generations a solid foundation upon which to build by serving as a bridge from our past to our future in order that our history, culture, traditions, and way of life are passed on to them.

“In order that we attain these noble and populist goals, we have determined that certain members of our Imperial Family, as well as certain of our countrymen who love and are concerned about the welfare of our People should participate in this work.”

In this document, His Majesty Ahma Selassie I named Prince Bekere Fikre-Selassie as Viceroy and Prince Ermias Sahle-Selassie Haile-Selassie as President of the Crown Council.

Amha Selassie, as Alga Worrach (Crown Prince) Asfa Wossen, had been active in government before that time. At age 20, he led Ethiopian troops against the invading Italians, and continued after the Italian occupation to organise resistance. And after the liberation of Ethiopia in 1941, he took an active part in the reconstruction of the country, with posts such as Governor-General and Viceroy of Begémder and Semien governorates (now known as Gonder and Tigré regions). He was President of the Ethiopian Red Cross, and represented Ethiopia internationally on many occasions. He had been appointed Meridazmatch — in its military form a title now roughly equivalent to colonel — on January 22, 1931, having been proclaimed Crown Prince (Alga Worrach,) and Heir Apparent on November 2, 1930.

For someone like the Alga Worrach, however, receiving the title of Meridazmatch, sometimes transliterated as Merid Azmatch, was highly significant. The title was the ancient rank of the Rulers of Shoa until Meridazmatch Sahle Selassie became Negus in 1813. The title Merid basically means “prince”; Azmatch basically means “advance”. In essence, then, a Merid Azmatch always had military leadership connotations: a prince at the head of the advance force of troops.

Crown Prince Asfa Wossen was named by his father, Emperor Haile Selassie, to the Crown Council, where he was to serve for many years. In this capacity, apart from his other duties, he became well-versed in the constitutional functions of the Council and its importance in the succession process.

Crown Prince Asfa Wossen was the only Ethiopian leader to have declared his accession to the Imperial Throne from outside the country. Had he done so earlier — under the tumultuous circumstances of 1975, after his father was killed — this may have been a rallying point for the international community. As it transpired, his gesture was too late to be given the credibility and power it sought. He was, nonetheless, widely loved and respected as a true Ethiopian patriot who had made considerable contributions to his country during his time there before the coup.

Alga Worrach Asfa Wossen’s elevation to the Throne, sanctioned by the Crown Council of the time, had an unquestioned constitutional validity. The Constitution of 1931 clearly spelled out the fact that only the Haile Selassie line of the Solomonic bloodline would henceforth represent the Crown of Ethiopia. This was the Ethiopian constitution which had been internationally accepted and recognised. Furthermore, the Crown Council’s function in endorsing or ratifying the elevation of a proper candidate, such as Alga Worrach Asfa Wossen, was clearly spelled out in the Constitution as adopted in 1955 and the Constitution which was to have been further amended in 1974 — after an extensive constitutional debate — when the Dergue seized power illegally.

The Crown Council which Emperor Amha Selassie I reconstituted in 1993 in exile — replacing many of the members who had either been killed during the coup and civil war, or who had died or retired subsequently — is today, then, the body which is constitutionally-charged with presenting the selected candidate for accession to the Throne for approval by the Ethiopian people.

“The Crown Council, the least clearly-defined advisory body [in Ethiopian government], nonetheless has potential power,” analyst George A. Lipsky wrote in 1962.4Lipsky, George A.: Survey of World Cultures, No.9: Ethiopia. New Haven, Connecticut, USA, 1962: Human Relations Area Files, Inc. “It consists, according to the Revised Constitution [of 1955], of the Primate of the Church (the Abuna), the President of the Senate, and ‘such Princes, Ministers, and Dignitaries’ as may be designated by the Emperor. It does not meet regularly, and is given little publicity. Presumably, it is convened only when fundamental issues of legislation or major questions of policy must be considered. Apart from the Emperor, the Council is the most important surviving element of the traditional form of imperial government.” [Italics added.]

Today, the Crown Council has made it clear that it will not present any nomination for succession to the Throne until the situation inside Ethiopia changes, and it becomes clear that the new Emperor can be named, and crowned by the Ethiopian Orthodox Church, on Ethiopian soil. As a result, it is the Crown Council, chaired in exile by HIH Prince Ermias Sahle-Selassie Haile Selassie, a grandson of the late Emperor, which is the “voice of the Crown”. Significantly, it was Crown Prince Asfa Wossen’s 1993 revitalisation of the Council and his appointment of Prince Ermias which gave continued life and hope to the Monarchy and ensured that the institution was left with a legal structure and leadership.

So the position of Emperor of Ethiopia is currently unfilled, with the Crown Council currently acting on behalf of the Crown. Article Eight of the 1955 Constitution noted: “Regency shall exist in the event that the Emperor is unable to exercise the imperial office, whether by reason of minority, absence from the empire, or reason of serious illness as determined by the Crown Council.”5Ethiopian Constitution, as amended in 1955. For a complete text of the 1955 Constitution, refer to the book Ethiopia and Haile Selassie, published in 1972 by Facts on File, New York. The editor of the book was Peter Schwab.

Ethiopian leaders have been known abroad as “Emperors”, but this is obviously a Western translation of the Ethiopian term for the leader of the Ethiopian Empire. Kings and emirs, rases, abetu, and dejazmatches or dejatches have ruled various regions and states which have comprised the Empire, with the Amhara, Shoa Amhara and Tigré kings always maintaining their links to the bloodline of Solomon and Makeda of Ethiopia.

The supreme leader among the Ethiopian nations, the King of Kings, is titled, in Amharic, Negusa Negest ze Ethiopia. And this is only loosely translated as “Emperor”. There is a parallel with the Iranian title of Shahanshah: King of Kings, again, loosely translated in the West as “Emperor”.

Crown Prince Asfa Wossen was never to sit on the Throne of Solomon in Ethiopia as Emperor Amha Selassie I. He was crowned at a private ceremony in London. But he was able to take forward the work of his father in transforming the Ethiopian Monarchy into a constitutionally-accountable body. He had, in fact, taken a significant rôle in the governance of Ethiopia throughout his life as Crown Prince. It was within the modernisation of the Monarchy that Emperor Haile Selassie had originally reconstituted the Crown Council; his son, Crown Prince Asfa Wossen, later ensured that it had a functioning rôle within the context of a world committed to accountable democratic systems.

The Council, under the Presidency of His Imperial Highness Prince Ermias Sahle-Selassie Haile-Selassie, was, at the time of this writing (1998), comprised of a number of princes of the Blood, as well as Ethiopian scholars and personalities. All had been appointed by Asfa Wossen, before his death in 1997. The reinvigorated Crown Council took the responsibility of the Monarchy seriously and, in 1996 while His Majesty was still alive, began strenuous attempts to fulfil its constitutional duty to Ethiopian citizens and the Ethiopian Church.

To this end, the Crown Council, immediately began assembling comprehensive records and written codification of the nation’s and the Crown’s Royal and Imperial structures, titles, ranks and symbols, as well as the order of precedence. The archives of the Imperial administrations, in Addis Ababa, were, because of the interregnum, unavailable for the time being, and so the process has involved an exhaustive study of available literature, records and institutional memory from outside of the old archives.

Today, during the interregnum, the national Order of Precedence is in the process of redefinition. The Emperor is represented by the Viceroy or the President of the Imperial Crown Council, indicating that the Throne of Solomon is not vacant nor in abeyance. The alignment to left and right of the Throne, then, is at the discretion of the President of the Council until the Council presents a successor to the Throne and he is approved by the Ethiopian people. The interregnum, and resultant diaspora of the Ethiopian hierarchy and many of the people of the country, also means that the creation of a comprehensive Order of Precedence is for the moment academic. Nonetheless, the Agafari to the Crown Council in Exile must still be cognisant of Ethiopian tradition when arranging functions.

The President of the Crown Council therefore may delegate or dictate a ceremonial Order of Precedence to suit a particular formal occasion. This may not necessarily correspond to a “chain of command”, which was implied by the traditional understanding of an Order of Precedence. The President’s wishes for any specific occasion would be interpreted in protocol terms by the Agafari to the Crown. In Western terms, the Agafari is today specifically styled as the Chief of Protocol.

Indeed, the Order of Precedence has only to do with the proximity of an individual to the Throne in formal gatherings. While this implies the relative disposition of the individual to the centre of power, this is not in reality the case. And the Order of Precedence is not necessarily linked to succession of the Crown, although it is logical that the candidates for succession would be arrayed to the Throne’s right.

Historically, although Emperors of Ethiopia have nominated their candidate for successor as Crown Prince, it has never been the case in the country that the process of primogeniture — right of succession going to the eldest son — has been automatically accepted. Indeed, the succession of the eldest son to the Throne has proven the exception rather than the rule.

“Though the principle of primogeniture was to some extent operative the throne could normally be inherited by any of the ruler’s male offspring. The resultant multiplicity of heirs was often a source of considerable intrigue and instability. Succession conflicts, Taddesse Tamrat notes, were in fact ‘endemic in mediæval Ethiopia’.”6Pankhurst, Richard: A Social History of Ethiopia. Op Cit. p.27.

At all times in Ethiopian history, succession has been required to be approved, either by the church or by other powers. In modern history, the presentation of the successor to the Throne has been codified in the Constitution as being the duty of the Crown Council. And, under the Constitution of 1955, and recently reaffirmed (in 1998) by the legal interpretation of the Afe-Negus and former Chief Justice of Ethiopia, Teshome Haile Mariam, the Council is obligated to ensure that the candidate for succession is “physically and mentally capable of assuming and maintaining the office” of Emperor.

“Primogeniture does not apply necessarily in Ethiopia in the Royal Family, with the nobility, or even with families of lesser note.”7Southard, Addison E., in Modern Ethiopia, in June 1931 National Geographic. Op Cit.

In a statement for the record in May 1998, Afe-Negus Teshome Haile Mariam noted:8HH Prince Asfa-Wossen Asserate, in correspondence to the author, June 30, 1998

“The Crown has been the national institution which secured the unity, sovereignty and sanctity of the Ethiopian people throughout their long history.

“From generation to generation, the Ethiopian Crown was vested in successive Emperors. As history clearly demonstrates, the successive Emperors carried out the great responsibilities of their position with the advice of their respective Crown Councils. And during an interregnum full responsibility for the guardianship of the Crown devolved upon the Crown Council.

“At the death of His Imperial Majesty the Emperor Haile Selassie I, it was the Crown Council which formalised the accession, in exile, of the former Crown Prince Asfa Wossen to the Throne, as His Imperial Majesty the Emperor Amha Selassie I. The action of the Crown Council in legitimising the accession of His Imperial Majesty the Emperor Amha Selassie I, now departed, well illustrates its historical rôle in protecting the Crown and ensuring its continuity.

“In choosing to strengthen the rôle of the Crown Council during the exile of the dynasty, the Emperor Amha Selassie I relied upon well-established historical precedent and tradition. In appointing his nephew, His Imperial Highness Prince Ermias Sahle-Selassie Haile Selassie, grandson of HIM Emperor Haile Selassie I, as President of the Crown Council, and naming His Imperial Highness Prince Bekere Fikre-Selassie as Viceroy, His Imperial Majesty Emperor Amha Selassie I wished to ensure that, at a time of enormous suffering by the Ethiopian People, the Crown would continue, despite the exile of the dynasty, to play as vigorous and constructive a rôle as possible in the reconstruction of the nation and would remain a visible symbol of Ethiopia’s history, traditions and culture. His Imperial Majesty, a Monarch of great vision, was very mindful of his own failing health and other circumstances, and was thus adamant that these conditions must not result in even a temporary eclipse of the Crown. In this way, His Imperial Majesty confirmed and strengthened the precedent by which the Crown Council, in the event of the death or incapacitation of the Emperor or his heir, acts as guardian of the Crown and assures its continuity. His Imperial Majesty thus laid a firm foundation which would serve as a bridge of Ethiopian heritage to the future generations.

“Based upon the responsibilities and powers vested in it by the late Emperor Amha Selassie, the Crown Council, during the current interregnum, has full authority to act as guardian of the Crown. In particular, the members of the Crown Council have both the authority and duty to

- Provide visible leadership on matters affecting Ethiopia and its Monarchy;

- Strengthen the role of the Crown inside and outside of Ethiopia, and remain in communication with leaders of foreign countries who might be able to assist the Ethiopian people in their current plight;

- Ensure that the Crown remains and be seen to remain the key to unity and reconciliation among the major groups and institutions of which the Ethiopian people and Ethiopian national life are composed;

- Play a leading rôle in legitimate efforts to safeguard the historical, cultural and religious patrimony of Ethiopia;

- “Identify key individuals who might be capable of assisting in these efforts, and to recognize and honor publicly or privately those individuals who have so assisted.”

Crown Prince Asfa Wossen had himself never been President of the Crown Council. However, it is likely that he chaired meetings of the Crown Council between 1957 and 1972, when his father Emperor Haile Selassie (who was at the time the Chairman) was absent.

Between 1941 and 1957, the President of the Imperial Crown Council (ICC) was Le’ul Ras Kassa Hailu, the Premier Prince of the Empire, who preceded even the Crown Prince in rank, and for whom every Friday afternoon between three and six o’clock, time was allocated in the Emperor’s schedule. This continued until Le’ul Ras Kassa Hailu died in 1957.9HH Prince Asfa-Wossen Asserate, in correspondence to the author, June 30, 1998. Between 1957 and 1972, the position of President of the ICC was vacant, with the Emperor himself chairing the Council’s meetings. In 1972, Le’ul Ras Asserate Kassa, the son of Le’ul Ras Kassa Hailu, was appointed President of the Council.10HH Prince (Le’ul) Asfa-Wossen Asserate, the historian now resident in Germany, is the son of Le’ul Ras Asserate Kassa and the grandson of Le’ul Ras Kassa Hailu. Under Emperor Ameha Selassie Afe Negus Teshome Haile Mariam acted as the President of ICC until 1993 when HIH Prince Ermias Sahle-Selassie was appointed by Emperor Ameha Selassie as the President of the Crown Council.

The Afe-Negus had worked closely with Emperor Amha Selassie in the 1993 reconvening the Crown Council, of which the Afe-Negus had himself once been President, under Emperor Amha Selassie.

The selection in 1993 of the Imperial Crown Council’s new President and Viceroy was particularly sensitive, and Emperor Amha Selassie had been aware, the Afe-Negus said, that the President of the Council — and the Council itself — would be responsible for maintaining the historic dignity continuation of the Crown in service to the Ethiopian people. Given that he was in his late seventies at the time, and in poor health (as the Afe-Negus’s statement indicated), the Emperor knew that Prince Ermias Sahle-Selassie would very soon be shouldering the full burden of office, albeit in exile.11This interpretation is based on conversations which the author had with the Emperor and Afe-Negus in 1992-93, and with the Afe-Negus in 1998.

The Afe-Negus confirmed, too, the Emperor’s explicit recognition of the Constitutional dictate that the Crown Council could only sanction a candidate for the Throne who was physically and mentally capable of assuming the office.

Alga Worrach Asfa Wossen’s own accession to the Throne was the first such enthronement in Ethiopian history to have taken place outside the Empire: it occurred in a quiet ceremony in London in 1988. But in some respects it accorded with the antique Ethiopian custom of being crowned where circumstances dictated. “Monarchs were usually crowned at the principal church in the area where they found themselves at the time of their accession to power. Emperor Zara Yaqob, however, reinstated an ancient tradition when he went in 1434 to be crowned at the ancient city of Axum, and thus invested the monarchy, as Taddesse Tamrat12Taddesse Tamrat is one of the foremost modern Ethiopian historians, publishing extensively in the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s. notes, with the prestige associated with the country’s old, historical religious and political capital. Several subsequent rulers followed this tradition, among them Sarsa Dengel (1563-1579) whose chronicle presents a graphic picture of the ceremonial. It states that the monarch, on reaching the vicinity of Axum, sent a message to the priests of the city, stating that he was ‘to celebrate the royal ceremonies in front of my mother, Seyon, tabernacle of the God of Israel, as did my fathers [ie: ancestors] David and Solomon.”13Pankhurst, Richard: A Social History of Ethiopia. Op Cit. pp27-28.

But Zara Yaqob’s revival of the tradition of a coronation in Axum was by no means absolute, and Ethiopia reverted to the pattern of choosing the enthronement site based on other political or personal exigencies of the day. This is what Alga Worrach Asfa Wossen was forced to do: his coronation in London in 1988 was conducted in less-than-formal circumstances, occasioned by his exile.

The Dergue, which grabbed power illegally and by force, and which had no legitimacy or historic or legal claim or right to office or authority, declared in March 1975 that it had deposed Emperor Haile Selassie I. Significantly, the Dergue announced that, having deposed Emperor Haile Selassie, it now recognised as Negus (King) the legitimate and constitutional successor to the throne, Crown Prince Asfa Wossen, who was in Geneva at the time for medical treatment. An announcement by the Dergue said that Crown Prince Asfa Wossen would be crowned King (Negus) immediately upon his return to Ethiopia. But the civil war and terror which swept over Ethiopia precluded any return by the Crown Prince who, having suffered a serious stroke, could not at that time travel.

By the time he was sufficiently well, it became clear that the Monarchy could not displace the Dergue for the moment because of the purge of former Government officials, the ongoing war and Soviet involvement. Under such circumstances, the Crown Prince could not return home.

The internationally- and historically-recognised Monarch and Monarchy did not abdicate; nor did the legal Constitution change, but the illegal act of an outlaw power group effectively altered the realities on the ground in Ethiopia. The subsequent military victory finalised against the Dergue on May 27, 1991, by guerilla fighters of the Tigré People’s Liberation Front (TPLF), a Tigrean organisation riding into Addis Ababa with two divisions of Sudanese armour (much as Tito had ridden into Belgrade in 1945 atop Soviet Red Army T-34 tanks), meant that a new de facto and unelected, unrepresentative power had come into control of Ethiopia.

The international community had what it felt were more important things to ponder in the middle of 1991 than the restoration of Ethiopian legitimacy. The collapse of the Soviet Union, the Dergue’s backers, meant that all attention was focused on the break-up of the Soviet empire and the spin-offs from that, including the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait in August 1990.

After 17 years of bloodshed and anguish in Ethiopia, a distracted international community — led, as far as Ethiopian discussions were concerned, by Britain and the US — allowed the TPLF to attempt to build an interim national administration in the country. [The TPLF later reconstituted itself, mostly for the purpose of retaining power over all of Ethiopia, to the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF).] The United States, in particular (and under then US Assistant Secretary of State for Africa Herman Cohen), stood by the TPLF leader, Meles Zenawi, and allowed him to consolidate power, riding roughshod over the claims and positions of other groups. In reality, the US and UK had few options; they were preoccupied with the break-up of the Soviet Empire and the emergence of troublesome leaders elsewhere, particularly Iraqi President Saddam Hussain’s military lunge at Kuwait, which required all the efforts of the US Bush Administration to control. Ethiopia’s restoration to traditional and democratic government was one of the casualties of this situation, as was the Liberian civil war on Africa’s West Coast. The US, totally focusing its resources on Iraq and Kuwait, asked Nigeria to handle the Liberian war.

But as a result of the TPLF victory, the Tigrean leadership also acceded to the wishes of their Eritrean fellow rebels fighting to make Eritrea independent. Eritrea formally seceded from Ethiopia in 1993. TPLF leader Meles Zenawi declared himself President of Ethiopia in July 1991 and moved to consolidate this de facto leadership with a series of carefully-orchestrated elections which occurred during a process of strict suppression of opposition voices and strong moves to stop the Monarchy from returning to the office and station it had held for three millennia. [Meles Zenawi’s subsequently changed his Administration’s structure, placing power in the hands of a Prime Minister, which he himself became, making the presidency ceremonial.] The TPLF had originally cast the Monarchy as one of the options in its proposed new constitution. But it was clear that the TPLF had merely inserted the Monarchy as an option only to be able to immediately dismiss it, as though it had been proffered to the people for debate. It had not. There was no possibility at that time of any popular discussion of the option, and the TPLF — which transformed into the EPRDF — ramrodded its “constitution” into effect without due process. The object was solely to give a patina of domestic and international legitimacy to the new EPRDF constitution. The so-called constitutional consultative assemblies were fraught with many problems during this highly-unstable period, and the EPRDF, as the ruling party de facto, made sure that no chance was given to any option other than those which it chose.

It is significant to note that the Monarchy has not relinquished its role and duties in Ethiopia. Since 2004, the Crown Council has redefined the role that a Constitutional Monarchy can play in Ethiopia that is much more in line with the role that constitutional Monarchs play in other countries.

It seems clear that had the exiled Crown Prince Asfa Wossen been physically fit, then the Monarchy could have taken a far greater rôle in ousting the Dergue and restoring legitimate government to Ethiopia in 1991 or earlier. The Crown Prince had been abroad during the 1974 coup receiving medical treatment for a stroke, brought about by complications from diabetes in 1973.14The Passing of An Era: A Short Biography of Emperor Amha Selassie I (1916-1997), in Ethiopian Review, January-February 1997.

.

Indeed, the Dergue’s removal was only possible in 1991 because of the withdrawal of Soviet support from it, brought about by the collapse of the USSR itself. The TPLF was not Ethiopia’s saviour; the NATO-led escalation of the Cold War against the Soviet Union had merely robbed the Dergue of its benefactor. History will show that Crown Prince Asfa Wossen’s physical disabilities — he was heavily paralysed from the stroke until the time of his death in 1997 — played a decisive rôle in Ethiopia’s history.

Despite being in exile in London, Crown Prince Asfa Wossen was persuaded, in 1988, to declare himself Emperor, taking the throne name Amha Selassie I. But this act, which showed that the Monarchy was still alive and evolving, did not have enough power behind it — because of the new Emperor’s poor health — to have sufficient political impact inside Ethiopia to bring about change on the ground. Emperor Amha Selassie did have the authority, under the Constitution of the internationally-recognised Government of Emperor Haile Selassie, to reconvene the Crown Council.

Writers Chris Prouty and Eugene Rosenfeld noted in their comprehensive Historical Dictionary of Ethiopia and Eritrea:15Prouty, Chris, and Rosenfeld, Eugene: Historical Dictionary of Ethiopia and Eritrea. 2nd Ed. 1989, Metuchen, New Jersey, and London: Scarecrow Press “Rulers in ancient times [in Ethiopia] usually had a close circle of people they trusted and consulted, but a Crown Council as such was named as an advisory body to the Emperor only in the revised Constitution of 1955. It was in existence since 1941… In 1966 new members were named. It was revived as the consultative body for the Emperor.”

It was given fresh life once again by Amha Selassie’s promulgation of July 15, 1993, appointing new names to the Council to give it the vitality to undertake meaningful actions to help Ethiopia. Clearly, the members of the Crown Council convened under Emperor Haile Selassie were no longer able, because of the civil war, to be brought together, although the institution of the Crown Council — like the Crown itself — retained its legal rôle.

The reconstruction of the Crown Council may have been Emperor Amha Selassie’s most significant contribution to Ethiopia after the 1974 coup. It was done with considerable deliberation and consultation, spearheaded by Afe-Negus Teshome Haile-Mariam, the former Chief Justice of Ethiopia under Emperor Haile Selassie I. He had been commanded by the new Emperor to canvas the Ethiopian community, inside and outside the country, for names to consider for the Council, and it was after an extensive procedure and series of discussions with the Emperor that a slate was put forward for consideration and, ultimately, acceptance on July 15, 1993, when His Majesty signed the document reconstituting the Council.

In the document of Appointment of the Ethiopian Crown Council 16Appointment of the Ethiopian Crown Council, English Translation, dated July 15, 1993. See illustration of the Amharic original shown here. His Majesty Ahma Selassie I said:

In order for Ethiopian sovereignty and unity to be respected, for the People’s well-being to be protected, and for the overall growth and development of our nation, we have strived ever since our appointment as Crown Prince of the Imperial Government of Ethiopia to serve our country and People as did the august Father His Imperial Majesty Haile Selassie I. The Ethiopian People’s life is our life; their happiness, ours; their suffering, our burden; their death, ours. We have no independent life apart from our People, neither do we wish it. What we wish and aspire for is for the Ethiopian People to live in peace and harmony. It is our current intention and wish to see to it that what we have started reaches fruition.

For well-known reasons, even if we are not amidst our People, we have never left them in spirit. In exile, we have shared our People’s tribulation and suffering.

Even now, we have firmly decided and are determined to be amidst our People to share with them their problems and to partake in their joys as well as to give them moral support, to facilitate their unity of purpose and to preserve their historical unity and for the People to rise and reconstruct our nation. It is our wish that for such as the Lord permits us, we will do all we can to leave for future generations a solid foundation upon which to build by serving as a bridge from our past to our future in order that our history, culture, traditions, and way of life are passed on to them.

“In order that we attain these noble and populist goals, we have determined that certain members of our Imperial Family, as well as certain of our countrymen who love and are concerned about the welfare of our People should participate in this work.”

In this document, His Majesty Ahma Selassie I named Prince Bekere Fikre-Selassie as Viceroy and Prince Ermias Sahle-Selassie Haile-Selassie as President of the Crown Council.

Amha Selassie, as Alga Worrach (Crown Prince) Asfa Wossen, had been active in government before that time. At age 20, he led Ethiopian troops against the invading Italians, and continued after the Italian occupation to organise resistance. And after the liberation of Ethiopia in 1941, he took an active part in the reconstruction of the country, with posts such as Governor-General and Viceroy of Begémder and Semien governorates (now known as Gonder and Tigré regions). He was President of the Ethiopian Red Cross, and represented Ethiopia internationally on many occasions. He had been appointed Meridazmatch — in its military form a title now roughly equivalent to colonel — on January 22, 1931, having been proclaimed Crown Prince (Alga Worrach,) and Heir Apparent on November 2, 1930.

For someone like the Alga Worrach, however, receiving the title of Meridazmatch, sometimes transliterated as Merid Azmatch, was highly significant. The title was the ancient rank of the Rulers of Shoa until Meridazmatch Sahle Selassie became Negus in 1813. The title Merid basically means “prince”; Azmatch basically means “advance”. In essence, then, a Merid Azmatch always had military leadership connotations: a prince at the head of the advance force of troops.

Crown Prince Asfa Wossen was named by his father, Emperor Haile Selassie, to the Crown Council, where he was to serve for many years. In this capacity, apart from his other duties, he became well-versed in the constitutional functions of the Council and its importance in the succession process.

Crown Prince Asfa Wossen was the only Ethiopian leader to have declared his accession to the Imperial Throne from outside the country. Had he done so earlier — under the tumultuous circumstances of 1975, after his father was killed — this may have been a rallying point for the international community. As it transpired, his gesture was too late to be given the credibility and power it sought. He was, nonetheless, widely loved and respected as a true Ethiopian patriot who had made considerable contributions to his country during his time there before the coup.

Alga Worrach Asfa Wossen’s elevation to the Throne, sanctioned by the Crown Council of the time, had an unquestioned constitutional validity. The Constitution of 1931 clearly spelled out the fact that only the Haile Selassie line of the Solomonic bloodline would henceforth represent the Crown of Ethiopia. This was the Ethiopian constitution which had been internationally accepted and recognised. Furthermore, the Crown Council’s function in endorsing or ratifying the elevation of a proper candidate, such as Alga Worrach Asfa Wossen, was clearly spelled out in the Constitution as adopted in 1955 and the Constitution which was to have been further amended in 1974 — after an extensive constitutional debate — when the Dergue seized power illegally.

The Crown Council which Emperor Amha Selassie I reconstituted in 1993 in exile — replacing many of the members who had either been killed during the coup and civil war, or who had died or retired subsequently — is today, then, the body which is constitutionally-charged with presenting the selected candidate for accession to the Throne for approval by the Ethiopian people.

“The Crown Council, the least clearly-defined advisory body [in Ethiopian government], nonetheless has potential power,” analyst George A. Lipsky wrote in 1962.17Lipsky, George A.: Survey of World Cultures, No.9: Ethiopia. New Haven, Connecticut, USA, 1962: Human Relations Area Files, Inc. “It consists, according to the Revised Constitution [of 1955], of the Primate of the Church (the Abuna), the President of the Senate, and ‘such Princes, Ministers, and Dignitaries’ as may be designated by the Emperor. It does not meet regularly, and is given little publicity. Presumably, it is convened only when fundamental issues of legislation or major questions of policy must be considered. Apart from the Emperor, the Council is the most important surviving element of the traditional form of imperial government.” [Italics added.]

Today, the Crown Council has made it clear that it will not present any nomination for succession to the Throne until the situation inside Ethiopia changes, and it becomes clear that the new Emperor can be named, and crowned by the Ethiopian Orthodox Church, on Ethiopian soil. As a result, it is the Crown Council, chaired in exile by HIH Prince Ermias Sahle-Selassie Haile Selassie, a grandson of the late Emperor, which is the “voice of the Crown”. Significantly, it was Crown Prince Asfa Wossen’s 1993 revitalisation of the Council and his appointment of Prince Ermias which gave continued life and hope to the Monarchy and ensured that the institution was left with a legal structure and leadership.

So the position of Emperor of Ethiopia is currently unfilled, with the Crown Council currently acting on behalf of the Crown. Article Eight of the 1955 Constitution noted: “Regency shall exist in the event that the Emperor is unable to exercise the imperial office, whether by reason of minority, absence from the empire, or reason of serious illness as determined by the Crown Council.”18Ethiopian Constitution, as amended in 1955. For a complete text of the 1955 Constitution, refer to the book Ethiopia and Haile Selassie, published in 1972 by Facts on File, New York. The editor of the book was Peter Schwab.

Ethiopian leaders have been known abroad as “Emperors”, but this is obviously a Western translation of the Ethiopian term for the leader of the Ethiopian Empire. Kings and emirs, rases, abetu, and dejazmatches or dejatches have ruled various regions and states which have comprised the Empire, with the Amhara, Shoa Amhara and Tigré kings always maintaining their links to the bloodline of Solomon and Makeda of Ethiopia.

The supreme leader among the Ethiopian nations, the King of Kings, is titled, in Amharic, Negusa Negest ze Ethiopia. And this is only loosely translated as “Emperor”. There is a parallel with the Iranian title of Shahanshah: King of Kings, again, loosely translated in the West as “Emperor”.

Crown Prince Asfa Wossen was never to sit on the Throne of Solomon in Ethiopia as Emperor Amha Selassie I. He was crowned at a private ceremony in London. But he was able to take forward the work of his father in transforming the Ethiopian Monarchy into a constitutionally-accountable body. He had, in fact, taken a significant rôle in the governance of Ethiopia throughout his life as Crown Prince. It was within the modernisation of the Monarchy that Emperor Haile Selassie had originally reconstituted the Crown Council; his son, Crown Prince Asfa Wossen, later ensured that it had a functioning rôle within the context of a world committed to accountable democratic systems.

The Council, under the Presidency of His Imperial Highness Prince Ermias Sahle-Selassie Haile-Selassie, was, at the time of this writing (1998), comprised of a number of princes of the Blood, as well as Ethiopian scholars and personalities. All had been appointed by Asfa Wossen, before his death in 1997. The reinvigorated Crown Council took the responsibility of the Monarchy seriously and, in 1996 while His Majesty was still alive, began strenuous attempts to fulfil its constitutional duty to Ethiopian citizens and the Ethiopian Church.

To this end, the Crown Council, immediately began assembling comprehensive records and written codification of the nation’s and the Crown’s Royal and Imperial structures, titles, ranks and symbols, as well as the order of precedence. The archives of the Imperial administrations, in Addis Ababa, were, because of the interregnum, unavailable for the time being, and so the process has involved an exhaustive study of available literature, records and institutional memory from outside of the old archives.

Today, during the interregnum, the national Order of Precedence is in the process of redefinition. The Emperor is represented by the Viceroy or the President of the Imperial Crown Council, indicating that the Throne of Solomon is not vacant nor in abeyance. The alignment to left and right of the Throne, then, is at the discretion of the President of the Council until the Council presents a successor to the Throne and he is approved by the Ethiopian people. The interregnum, and resultant diaspora of the Ethiopian hierarchy and many of the people of the country, also means that the creation of a comprehensive Order of Precedence is for the moment academic. Nonetheless, the Agafari to the Crown Council in Exile must still be cognisant of Ethiopian tradition when arranging functions.

The President of the Crown Council therefore may delegate or dictate a ceremonial Order of Precedence to suit a particular formal occasion. This may not necessarily correspond to a “chain of command”, which was implied by the traditional understanding of an Order of Precedence. The President’s wishes for any specific occasion would be interpreted in protocol terms by the Agafari to the Crown. In Western terms, the Agafari is today specifically styled as the Chief of Protocol.

Indeed, the Order of Precedence has only to do with the proximity of an individual to the Throne in formal gatherings. While this implies the relative disposition of the individual to the centre of power, this is not in reality the case. And the Order of Precedence is not necessarily linked to succession of the Crown, although it is logical that the candidates for succession would be arrayed to the Throne’s right.

Historically, although Emperors of Ethiopia have nominated their candidate for successor as Crown Prince, it has never been the case in the country that the process of primogeniture — right of succession going to the eldest son — has been automatically accepted. Indeed, the succession of the eldest son to the Throne has proven the exception rather than the rule.

“Though the principle of primogeniture was to some extent operative the throne could normally be inherited by any of the ruler’s male offspring. The resultant multiplicity of heirs was often a source of considerable intrigue and instability. Succession conflicts, Taddesse Tamrat notes, were in fact ‘endemic in mediæval Ethiopia’.”19Pankhurst, Richard: A Social History of Ethiopia. Op Cit. p.27.

At all times in Ethiopian history, succession has been required to be approved, either by the church or by other powers. In modern history, the presentation of the successor to the Throne has been codified in the Constitution as being the duty of the Crown Council. And, under the Constitution of 1955, and recently reaffirmed (in 1998) by the legal interpretation of the Afe-Negus and former Chief Justice of Ethiopia, Teshome Haile Mariam, the Council is obligated to ensure that the candidate for succession is “physically and mentally capable of assuming and maintaining the office” of Emperor.

“Primogeniture does not apply necessarily in Ethiopia in the Royal Family, with the nobility, or even with families of lesser note.”20Southard, Addison E., in Modern Ethiopia, in June 1931 National Geographic. Op Cit.

In a statement for the record in May 1998, Afe-Negus Teshome Haile Mariam noted:21HH Prince Asfa-Wossen Asserate, in correspondence to the author, June 30, 1998

“The Crown has been the national institution which secured the unity, sovereignty and sanctity of the Ethiopian people throughout their long history.

“From generation to generation, the Ethiopian Crown was vested in successive Emperors. As history clearly demonstrates, the successive Emperors carried out the great responsibilities of their position with the advice of their respective Crown Councils. And during an interregnum full responsibility for the guardianship of the Crown devolved upon the Crown Council.

“At the death of His Imperial Majesty the Emperor Haile Selassie I, it was the Crown Council which formalised the accession, in exile, of the former Crown Prince Asfa Wossen to the Throne, as His Imperial Majesty the Emperor Amha Selassie I. The action of the Crown Council in legitimising the accession of His Imperial Majesty the Emperor Amha Selassie I, now departed, well illustrates its historical rôle in protecting the Crown and ensuring its continuity.

“In choosing to strengthen the rôle of the Crown Council during the exile of the dynasty, the Emperor Amha Selassie I relied upon well-established historical precedent and tradition. In appointing his nephew, His Imperial Highness Prince Ermias Sahle-Selassie Haile Selassie, grandson of HIM Emperor Haile Selassie I, as President of the Crown Council, and naming His Imperial Highness Prince Bekere Fikre-Selassie as Viceroy, His Imperial Majesty Emperor Amha Selassie I wished to ensure that, at a time of enormous suffering by the Ethiopian People, the Crown would continue, despite the exile of the dynasty, to play as vigorous and constructive a rôle as possible in the reconstruction of the nation and would remain a visible symbol of Ethiopia’s history, traditions and culture. His Imperial Majesty, a Monarch of great vision, was very mindful of his own failing health and other circumstances, and was thus adamant that these conditions must not result in even a temporary eclipse of the Crown. In this way, His Imperial Majesty confirmed and strengthened the precedent by which the Crown Council, in the event of the death or incapacitation of the Emperor or his heir, acts as guardian of the Crown and assures its continuity. His Imperial Majesty thus laid a firm foundation which would serve as a bridge of Ethiopian heritage to the future generations.

“Based upon the responsibilities and powers vested in it by the late Emperor Amha Selassie, the Crown Council, during the current interregnum, has full authority to act as guardian of the Crown. In particular, the members of the Crown Council have both the authority and duty to

- Provide visible leadership on matters affecting Ethiopia and its Monarchy;

- Strengthen the role of the Crown inside and outside of Ethiopia, and remain in communication with leaders of foreign countries who might be able to assist the Ethiopian people in their current plight;

- Ensure that the Crown remains and be seen to remain the key to unity and reconciliation among the major groups and institutions of which the Ethiopian people and Ethiopian national life are composed;

- Play a leading rôle in legitimate efforts to safeguard the historical, cultural and religious patrimony of Ethiopia;

- “Identify key individuals who might be capable of assisting in these efforts, and to recognize and honor publicly or privately those individuals who have so assisted.”

Crown Prince Asfa Wossen had himself never been President of the Crown Council. However, it is likely that he chaired meetings of the Crown Council between 1957 and 1972, when his father Emperor Haile Selassie (who was at the time the Chairman) was absent.

Between 1941 and 1957, the President of the Imperial Crown Council (ICC) was Le’ul Ras Kassa Hailu, the Premier Prince of the Empire, who preceded even the Crown Prince in rank, and for whom every Friday afternoon between three and six o’clock, time was allocated in the Emperor’s schedule. This continued until Le’ul Ras Kassa Hailu died in 1957.22HH Prince Asfa-Wossen Asserate, in correspondence to the author, June 30, 1998. Between 1957 and 1972, the position of President of the ICC was vacant, with the Emperor himself chairing the Council’s meetings. In 1972, Le’ul Ras Asserate Kassa, the son of Le’ul Ras Kassa Hailu, was appointed President of the Council.23HH Prince (Le’ul) Asfa-Wossen Asserate, the historian now resident in Germany, is the son of Le’ul Ras Asserate Kassa and the grandson of Le’ul Ras Kassa Hailu. Under Emperor Ameha Selassie Afe Negus Teshome Haile Mariam acted as the President of ICC until 1993 when HIH Prince Ermias Sahle-Selassie was appointed by Emperor Ameha Selassie as the President of the Crown Council.

The Afe-Negus had worked closely with Emperor Amha Selassie in the 1993 reconvening the Crown Council, of which the Afe-Negus had himself once been President, under Emperor Amha Selassie.

The selection in 1993 of the Imperial Crown Council’s new President and Viceroy was particularly sensitive, and Emperor Amha Selassie had been aware, the Afe-Negus said, that the President of the Council — and the Council itself — would be responsible for maintaining the historic dignity continuation of the Crown in service to the Ethiopian people. Given that he was in his late seventies at the time, and in poor health (as the Afe-Negus’s statement indicated), the Emperor knew that Prince Ermias Sahle-Selassie would very soon be shouldering the full burden of office, albeit in exile.24This interpretation is based on conversations which the author had with the Emperor and Afe-Negus in 1992-93, and with the Afe-Negus in 1998.

The Afe-Negus confirmed, too, the Emperor’s explicit recognition of the Constitutional dictate that the Crown Council could only sanction a candidate for the Throne who was physically and mentally capable of assuming the office.

Alga Worrach Asfa Wossen’s own accession to the Throne was the first such enthronement in Ethiopian history to have taken place outside the Empire: it occurred in a quiet ceremony in London in 1988. But in some respects it accorded with the antique Ethiopian custom of being crowned where circumstances dictated. “Monarchs were usually crowned at the principal church in the area where they found themselves at the time of their accession to power. Emperor Zara Yaqob, however, reinstated an ancient tradition when he went in 1434 to be crowned at the ancient city of Axum, and thus invested the monarchy, as Taddesse Tamrat25Taddesse Tamrat is one of the foremost modern Ethiopian historians, publishing extensively in the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s. notes, with the prestige associated with the country’s old, historical religious and political capital. Several subsequent rulers followed this tradition, among them Sarsa Dengel (1563-1579) whose chronicle presents a graphic picture of the ceremonial. It states that the monarch, on reaching the vicinity of Axum, sent a message to the priests of the city, stating that he was ‘to celebrate the royal ceremonies in front of my mother, Seyon, tabernacle of the God of Israel, as did my fathers [ie: ancestors] David and Solomon.”26Pankhurst, Richard: A Social History of Ethiopia. Op Cit. pp27-28.

But Zara Yaqob’s revival of the tradition of a coronation in Axum was by no means absolute, and Ethiopia reverted to the pattern of choosing the enthronement site based on other political or personal exigencies of the day. This is what Alga Worrach Asfa Wossen was forced to do: his coronation in London in 1988 was conducted in less-than-formal circumstances, occasioned by his exile.